"Bed rearrangement" at customs: what to expect from the latest reform and who profits from popular smuggling schemes.

The Ukrainian customs authorities are expecting another reform. At the end of October, a law on the customs reboot came into effect, which experts have high hopes for. Its aim is not so much to dismantle specific smuggling schemes but to generally try to eliminate them by changing the operational principles of customs authorities and introducing oversight from foreign experts.

"Telegraph" investigated which customs transactions currently cause the most losses to the Ukrainian budget, why they have not yet been halted, and what prospects the latest attempt at customs reform holds.

Gray Zone: Years of Reforms with Zero Effect

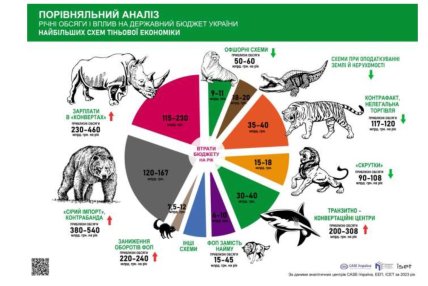

Customs equals corruption. This is the belief of the majority of Ukrainians, giving customs the top spot among the most corrupt and ineffective state structures in Ukraine. This is also confirmed by recent analytics prepared jointly by ISET, CASE Ukraine, and the "Economic Expert Platform" (EEP), which states that the largest annual turnover of shadow funds in the country – from 340 to 540 billion UAH – is attributed to illegal operations in the customs sector. Such operations are supposed to be prevented by the State Customs Service (SCS), yet for some reason, this is not happening.

In reality, the reasons for this "for some reason" have been known for a long time – customs has always been, and still remains, a feeding ground for corrupt SCS employees, and not just them. Corrupt customs schemes today are well integrated with law enforcement officers, local officials, and even high-ranking cabinet ministers, who, thanks to their powers, influence the work of customs and, consequently, are always eager to receive their "cut".

Thus, the demonstrative attempts to transform Ukrainian customs into "an effective tool for budget replenishment" and "a functional body against illegal schemes," which have been ongoing since Ukraine gained independence, mainly resembled the well-known meme "bees versus honey."

As a result of these attempts, the Ukrainian customs underwent several transformations, having been the State Customs Committee, later the State Customs Service, then a subordinate structure within the Ministry of Revenue and Duties and the State Fiscal Service. Finally, in 2019, it supposedly became a separate "new customs" again, reclaiming its former name of SCS.

Under President Zelensky, there were several public steps towards "systemic reform" of Ukrainian customs. For instance, in July 2019, then-Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman signed an order to implement measures for reforming the tax and customs services. In May 2020, a similar document was issued by the government of Denys Shmyhal, specifically for customs. The planned reform was supposed to address both changes to the organizational structure of customs authorities and enhance their institutional capacity and improve material support.

In addition to presenting general governmental plans, several concrete and effective measures were implemented to break the backbone of the corrupt foundation of Ukrainian customs. Experts consider such steps to include, for example, the appointment in 2019 of Max Nefyodov as head of the SCS, who was not tainted by customs scheming, mass layoffs in 2021 of employees and leaders most "exposed" to corruption in local SCS units, and the introduction of personal sanctions in 2021 and 2023 against the most active smuggling businessmen.

However, ultimately, even this did not help – the system "digested" these changes, and by the end of 2024, the Ukrainian customs border still remains porous to smuggling and a field for corrupt violations. The promised arrests of well-known smugglers and corrupt customs officers have yet to materialize. Even in a high-profile case like that of the "smuggling king" Vadim Alperin, both the "smuggling king" himself and one of the suspects in the case, former deputy head of the energy customs Alina Skomarova (who, by "strange" coincidence, is the sister of one of the heads of NABU detectives working on Alperin's case) remain at large. It is uncertain whether this case will not be closed soon, like many others before it.

Meanwhile, according to a study by ISET, "CASE Ukraine," and EEP, the annual losses to the budget due to the ineffective operation of the customs system (in particular, due to the shortfall in due taxes, customs duties, and excise taxes) range from 120 to 167 billion UAH/year, or over 4 billion dollars. Other experts report similar figures. Even pro-government politicians cite a figure of 100 billion. This is quite comparable to the missing amount that, if not completely closing, could significantly reduce the current gap in the Ukrainian budget. It seems that even the government and the Office of the President have finally recognized this, as they are known to be actively searching for "money for the war."

Perhaps this is precisely why the latest steps have been taken to improve customs operations, with several actions implemented recently. From attempts to block specific illegal export routes and increasing responsibility for smuggling, to legislative changes regarding the very operation of customs, which may have tectonic implications for the situation. One such "tectonic" change could be the Law "On Amendments to the Customs Code of Ukraine on Establishing the Specifics of Service in Customs Authorities and Conducting Certification of Customs Officials." Or, as it has been dubbed, the "law on customs reboot."

What Are We Fighting Against

Today, a whole system of circumventing customs rules operates at the Ukrainian border, meaning a system of violations of customs legislation, which is jointly utilized by both dishonest businesses to evade paying the relevant duties or taxes, as well as officials, primarily customs officers, who have their own corrupt interests in it. In this study by "CASE Ukraine," a concise yet sufficiently comprehensive classification of such schemes can be found. Specifically, in the area of illegal imports, analysts identified four main groups of illegal customs transactions.

Firstly, there is "distorted declaration" (movement concealed from customs control). This scheme involves manipulations with permit and accompanying documents for goods through intentional understatement of indicators – customs value, weight, quantity, as well as changing product characteristics and quality, or altering codes or subcategories of goods. As a result, the importer can significantly understate the customs payments due. According to experts, one of the features of this scheme is the involvement of corrupt customs officials.

Secondly, there is movement outside customs control ("black smuggling"). In this case, "black smugglers" include those who cross the border outside of checkpoints, as well as those whom customs officers allow through such checkpoints without checks, in exchange for bribes.

Thirdly, there is abuse of privileges granted by both international agreements and domestic legislation. For example, this may involve disguising industrial batches of goods as personal imports ("suit jackets") or courier shipments, transport in diplomatic luggage ("diplomats"), schemes for importing under duty-free, under the guise of individual postal shipments ("mail"), etc. The involvement of customs officers in such schemes mainly consists of their "not seeing" them.

Fourthly, there is the so-called "interrupted import," where goods are imported for sale under regimes that do not foresee customs duties, but then "disappear," or their fictitious export is arranged. This scheme has several subtypes, including transit, temporary import or export, customs warehouse, processing on customs territory or outside customs territory. Such schemes are very difficult to trace, as when moving through customs control with documents, such batches of goods often appear to be in order, and the wonders begin only after entering the territory of Ukraine.

Regarding illegal exports, the research mentions that among the most dangerous are schemes of fictitious entrepreneurship, particularly "carousel fraud," which involves multiple resales of exported goods (sometimes only on paper) to recover VAT or simply not returning foreign currency earnings to the state. This issue has become particularly relevant due to the activation of "black grain traders," whose annual losses from their activities, according to various reports, can reach tens of billions of UAH. Often, the implementation of such schemes is linked to the lack of proper oversight over exported products or even the intentional ignoring of violations by responsible officials, including customs officers.

What and How Should the Customs Reboot Law Resolve

It is clear that the vast majority of the aforementioned schemes are impossible without the direct involvement of interested officials